By Orikron, Source: X page

The Wall Street Journal reported in October that Washington’s directives to move manufacturing out of China and dethrone it as the world’s factory are not achieving their desired results. WSJ: “Exports from China’s central and western provinces are growing faster than exports from rival manufacturing destinations.”

Funnily enough, of the “big three” manufacturing alternatives western ideologues have been touting (Vietnam, India, and Mexico), it is Communist Party-led Vietnam with a developmental model eerily similar to China’s (Socialist-Oriented market Economy vs Socialist Market Economy) that has found the most success in growing its share of the manufacturing pie while two of the “world’s largest [liberal] democracies” have struggled to get off their feet.

The United States has been subsidizing and providing other incentives to persuade businesses to leave China; instead, since 2018, exports from 15 of China’s central and western provinces have increased by 94% (!). Compared to India’s 41%, Mexico’s 43% and Vietnam’s 56%. Rather than crippling China, the United States is unintentionally helping it achieve one of its major stated goals: to eliminate “unbalanced and inadequate development” which, due to the nature of export-led development, has allowed the littoral regions to get rich first.

But China’s interior has another crucial advantage: its highly navigable inland waterways.

The Yangtze river alone, spanning 11 provinces, has a yearly cargo throughput of 3.59 billion tons. For comparison, the Suez canal stands at only 1.27 billion tons yearly.

The right analogue to China isn’t Japan; it’s Germany, with its rich and navigable interior waterways, that allowed it to become a pluricentric manufacturing power in the 20th century. Except that this “Germany” is 17 times bigger.

Furthermore, China isn’t resting on its geographical laurels. It has a 2500-year history of building canals to extend the interconnectivity of inland waterways (see the Grand Canal, dating back to the 5th century BCE and still in operation, at the top-right). It hasn’t lost this habit.

To give just one of many examples, the Pinglu Canal (bottom-left), will reduce the travel distance between Guangxi’s inland rivers to the Beibu Gulf by 560km — saving 10 days of travel time.

And will further reduce it by another 800km (by avoiding the detour through the Pearl River Delta) if the cargo is destined to ASEAN countries (which now account for an equal share of China’s exports to the United States; and the greatest share of its imports). Construction began in June of 2023 and it’s set to be operational by *2026.* These deadlines are rarely missed.

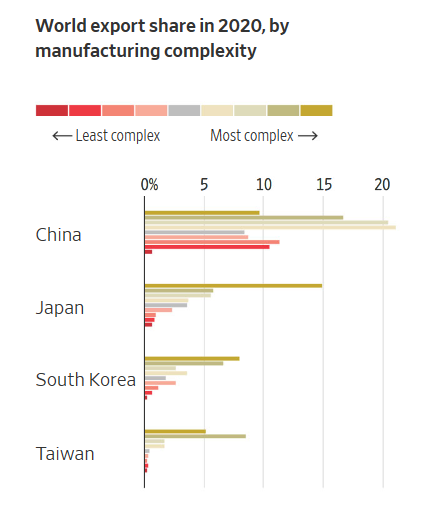

Further, China’s export share is no longer tied down to low-complexity goods, as it undergoes a massive state-led campaign of Industrial Upgrading which has already made it the dominant player in industries such as Solar and EVs.

The UN’s International Classification of All Economic Activities has divided all of human industry into listed 41 categories, 207 sub-categories and 666 sub-sub-categories.

China is the only country in the world that possesses all of them. Not everything is made in China, but anything is made in China. And it intends to keep it that way, for the purpose of self-reliance.

Putting aside self-reliance and national security, China is still able to stay internationally competitive in all these industries because of its state-led, investment-heavy planned economic development that provides the massive infrastructure, financing and innovation support that allows Chinese enterprises to cut costs even as workers’ compensation rises at an unprecedented pace for a large country.

This disproves the simple and innumerate narrative of a certain type of simpleton who believes that the drastic rise in compensation of Chinese workers will spell doom for its economy. Further, it adds depth to the analysis that China is merely “moving up the value” chain. It is better to understand it as building a civilizational-scale industrial system.

Further, China is now the world-leader, by far and away, in yearly robot installations and will soon rise to become the 3rd most robotized country per capita (behind only south Korea and Singapore, much smaller economies but ahead of Germany and Japan, its primary high-complexity manufacturing competitors).

The economic reasoning is solid: what’s a tripling in average compensation over the last 10 years matter when robot density multiples 100-fold? China understands that increasing standards of living, aggregate output, and economic diversity and self-reliance need not be competing goals.

Industry understands this too, as per the WSJ report:

“Logistics costs in China are a fraction of the cost in India, for example, which can’t match Chinese port and road infrastructure.”“My concern is very much about the newcomers,” said Stefan Angrick, senior economist at Moody’s Analytics in Tokyo. “How do you compete with that?”

“China is going to be a major player in global manufacturing for the foreseeable future,” said Gordon Hanson, an economist and professor of urban policy at Harvard University’s Kennedy School “China just has too much capacity for the world not to need to rely on it for a good while.”

Competent geopolitical-economy is the root of human development. Currently, 371 million Chinese citizens live in Very Highly developed provinces (UNDP’s HDI). This means that, in a sense, China is already the world’s largest *developed* country. And, with the industrialization of its vast interior, the remaining 1 billion will soon get to enjoy that same level of development.

To put that into perspective, the currently developed world (largely the West and its appendages), has a total of 1.3 billion. China is set to more than double the number of people living in developed countries by 2030. It’s no exaggeration to say this process will have the most impactful implications since the rise of the West 500 years ago; but with an entirely different model and ultimate aim.